First Hymn Explication

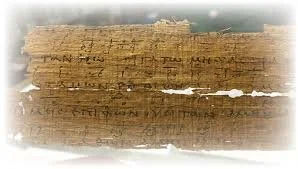

The First Hymn is an ancient trinitarian hymn to God found on a papyrus at Oxyrhynchus belonging to 3rd century Egyptian Christian culture. Thoroughly reflective of both its Graeco-Roman context and the early worshiping church, the hymn is our earliest example of Christian hymnody outside Scripture, and the very first musically notated Christian hymn. The hymn takes elements of familiar Graeco-Roman cultic worship formulae traditionally associated with Zeus and turns it on its head to make a full-throated paeon of Christian praise to the God of the Bible: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The effect of the poem is to assert the superiority of our God over Zeus in a kind of parody by at first imitating the cultic worship form and moving into a song that surges in trinitarian praise. Here is the hymn, as translated by Dr. John Dickson:

First Hymn

Let all be silent:

The shining stars not sound forth,

All rushing rivers stilled,

As we sing our hymn

To the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit,

As all Powers cry out in answer,

“Amen. Amen.”

Might, praise, and glory forever to our God,

The only Giver of all good gifts.

Amen. Amen.

The poem is divided into a basic 3-part lyric structure, with the first three lines calling for silence before the praise begins. The second section announces the hymn to the Trinity--God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit--and shows the powers of Heaven responding. The final three lines end the poem in doxology and ascribe all glory to God, entitling Him as the giver of all good gifts.

In the first section, we begin with a surprising silence. This first line announces from the outset that this poem of praise is turning Graeco-Roman cult worship on its head in praise of the one true God, as cult worship to Zeus always began with this call to silence. This paradoxical silence in the moment we might expect praise is also a reverse of the words of the psalmist in Psalm 19 (KJV), which declare that “the stars proclaim God’s handiwork.” Day to day pours forth speech. In fact, there is no language where this voice is not heard. However, in this couplet, the poet asks that the universe itself be silent before God. Christians will call to mind the famous advent hymn, “let all mortal flesh keep silence,” itself a reference to Habakkuk 2:20 and Zechariah 2:13, but in this case, even the stars are called to be silent before the creator of the universe. This is a strange request, but in the context of Graeco-Roman cult worship, the silence of the observers always comes first, lest any unheeding voice profane the ritual to come. In this instance, however, the creation itself is called to be silent before its creator God, before the praise of God's people can begin.

The next line extends the call to silence by calling on the rushing rivers to be stilled, an example of the poetic device of merism, where two extremes are mentioned--the stars in the universe on the one hand and the river on earth on the other--and everything in between is implied: A to Z and everything in between. Everything in creation must be silent, from the stars above to the rivers below. Psalm 46 tells us that the tumult of rushing waters, and the river “whose streams make glad the city of God,” point to our stability in God’s care for us (ESV). In this poem, all rushing rivers need to be silent as “we sing our hymn.” The contrast not only between the stars and the rivers but also between the rushing rivers and the silence of worshipers before Almighty God couldn’t be more pronounced. Not only are rushing rivers noisy, they are tumultuous. In order to worship aright, the poem exhorts, we paradoxically need to be quiet before our holy God.

The call for creation to be silent is only the first stage, however. The next section reverses this call and announces the subject of our hymn as God's people are to sing to “the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.” This is the climax to which the beginning points. Surely in its time this song would have made a startling claim. The ancient world was used to hymns to Zeus, but this is a full expression of worship to the trinitarian God of the Bible: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. This trinitarian formula is present in Christ’s great commission (Matthew 28:19), in John 1:1-4, and elsewhere in the Bible, but scholars can rejoice at this full expression of early belief in the Trinity in this early church hymn, long before the Nicene Council made it de rigeur for Christians everywhere to worship God as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. In addition, the fulness of this worship calls on all our faculties to worship, as we worship God in His fullness as Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

In the next two lines we are given a glimpse of the worship at the throne of God in Revelation 4, where all the elders cast down their crowns at His feet, crying “holy, holy, holy” and ascribing all praise to our God. Or in Isaiah 6, where the seraphim cry “holy” to the King (Isaiah 6:3). In this instance, however, all the powers are seen crying out in answer, saying “Amen, Amen.” In Scripture, we usually see the Powers as opposed to God’s goodness, such as in Romans 8 where nothing can separate us from His love, not even the powers (Romans 8:38-39). Ephesians 6:12 describes the Christian as wrestling “not against flesh and blood” but against the powers (KJV). In this song, however, the powers cry out in answer, “Amen. Amen.” They agree with the worshipping body singing to God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, in echo of Heavenly worship in Revelation or in Psalm 148, where all the Heavenly host praise Him (Psalm 148:1-2). In Colossians 1:16 we see that all rulers and authorities were created “by Him and for Him” (KJV). Here the powers are echoing the praise of the church, saying, “Amen, Amen.” This full-hearted submission and worship shows us how deep is the worship of Heaven: it not only includes us as the worshiping body, but all the heavenly host worship God, too: even the powers and principalities fall at His feet. Isn’t it amazing that at a time when we so desperately need Christ to “reveal [the church’s] unity, guard her faith, and preserve her in peace,” this early church expression of all creation’s praise is found and restored for us to sing? (BCP) This is a full expression of the great cloud of witnesses and communion of saints in a worship in which we participate with even the Heavenly Host during corporate hymn-singing.

The final section is one of doxology, ascribing “might, praise and glory forever to our God.” The Bible is full of such doxology, with the endings of most epistles being prime examples. One such example of doxology is I Chronicles 29:11, which says, "Yours, O Lord, is the greatness and the power and the glory and the victory and the majesty, for all that is in the heavens and on the earth is yours” (ESV). Or again in Jude: “to the only God, our Savior, through Jesus Christ our Lord, be glory, majesty, dominion, and authority before all time and now and forever, Amen” (ESV). In such doxology, it is as if the words of praise fall over themselves in expression as a grocery list of character qualities of our God. The most might, praise, and glory belong to Him. The poet cannot help praising Him with all the superlatives possible.

This section ends with referencing God, whom we have praised, as “the only Giver of all good gifts.” This is a bookending reference to the familiar formula of Graeco-Roman praise to Zeus which started our poem. In pagan worship, Zeus is often referred to as a giver. But in this case, the poet is turning the formula on its head. Our God is the only giver of all good gifts. Using the figure of rhetoric of what might seem to be hyperbole but is in fact absolute precision, we get the idea that God is the only true God, the only giver, and not only the only giver, but the only giver of all good gifts. Our poet is making a polemical argument by parodying cultic worship. Zeus may be said to be a giver of gifts, but in reality, our God is the only giver of all good gifts. Beyond referencing and playing with familiar ritual formulae, however, this line also points to James 1:17, which makes the claim that “all good gifts come from above, from the Father of Heavenly lights,” from whom there is no shadow of change (NIV). Biblically speaking, the all in all good gifts is one hundred percent accurate, and our poet knows it full well.

This paeon of praise known as the First Hymn gives us a glimpse into early Christian worship. This worship turns the familiar pagan world inside out by imitating the very songs of Graeco-Roman Zeus worship and going beyond them to show how great our only true God is. This praise invites God's people, created for the purpose of worshiping a good God, into the paradoxical expression of worship first in stillness then in doxology and praise, before ending with the triumphant claim that unlike Zeus, our God is the only Giver of all good gifts. In singing this hymn, we are participating in the earliest worship alongside brothers and sisters in Christ from ages past who have declared war on the empty pagan idolatries of their day. The Bible tells us that the gates of hell cannot prevail against such authoritative worship of our great God (Matthew 16:17-19). Doesn’t the Spirit within us groan in what words cannot utter, that God is our glorious King! Singing this hymn, we enter into the worship of the great company of Heaven, singing ‘holy, holy, holy is the Lord God Almighty. Heaven and earth are full of His glory.’ Amen, and Amen.